3 Hurricanes Trigger Labor Shortage

David R. Kotok, October 9, 2024

(The following was first published on The Kotok Report website and via LISTSERV. For details, visit https://kotokreport.com/.)

Rebuilding, cleanup, mitigation, maintenance, infrastructure repairs in 7 states will require 100s of thousands of additional people working. We need to import more labor, not deport. Fix DACA now. U7 says Labor market still tight, just less so than Covid shock. Congress must act quickly and stop politicizing the national economy and threatening the future. Now here’s a study lesson for serious Nerds. Praise and thanks to historian Philipa Dunne for her excellent assistance.

I’ve written about the U7 and about the use and construction of the employment statistics that are released at the beginning of each month. For those details see the BLS website, https://www.bls.gov/.

My friend Philippa Dunne of TLRanalytic sent this very insightful discussion and offered me permission to share it with our readers. I learned from Philippa that there once was a U7 in use and it was folded into the U6 about 30 years ago. So, we use the Danny Blanchflower method to reconstruct an estimate of the U7. For our previous writings about the U7 see “Claudia, Danny, Michael, The U7 & Me,” https://kotokreport.com/claudia-danny-michael-the-u7-me/.

Now here’s Philippa’s full discussion, and I thank her for offering it so I may share it with readers. For information about TLR and Philippa’s analysis, visit their website: https://www.tlranalytics.com/. You can subscribe to TLRwire for $27 a month. I recommend it. I read it regularly.

Here’s Philippa Dunne.

Hey David,

As I was reading through the old U-7 information, I thought it might be worth highlighting the evolution of BLS thought on unemployment rates, and what they intend to capture. Please use any of this if of interest.

Thanks for your piece about alternative measures of unemployment. I have mentioned to Danny that while I think his U-7 rate is very useful, it bothers me a bit that the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated their own U-7 rate between 1976 and 1995, then dropped it in favor of the U-6 rate, so I wish he had a different title. But since most people don’t know the progression of BLS thought once included U-7, it’s not really a problem. But beyond possible pedantry, the history of the various rates provides insight into the evolution of thinking among the economists and statisticians who work for us at the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The U-1 through U-7 rates were initially formulated by Julius Shiskin, the ninth commissioner of the BLS, who served from 1973 until his death in 1978. As you may know, he was the one who noted in a 1974 opinion piece he published in the New York Times that the BLS’s definition of a recession is “known to only a number of specialists in business cycle studies,” and that most people use a “simplistic” definition that has “worked quite well”: two quarters of negative GDP.

It’s worth taking a look at the article, which includes a reference to a “Louis Harris,” poll showing that 65% of American believed at the time that the country was in recession, supported by “herd facts,” including declining real output and rising unemployment,” and his note that although “almost everyone agrees we are in one…no one is saying what it is.” He outlines several formal definitions that could be used, but notes the National Bureau of Economic Analysis, who had been studying business cycles since the 1920s, remained reluctant to adopt “such specific criteria,” based on an “easily understood desire for flexibility.” And he is sensitive to the plight of the then-current president, who would have been Gerald Ford, who had to battle the complex problem of “declines in real output and rises in unemployment which are accompanied by rapidly rising prices.”

John E. Bregger and Steven E. Haugen detailed the new rates, and the retirement of the U-7, in a 1995 Monthly Labor Review. In describing the requirement that someone look for a job in order to be counted as unemployed, they note that “the inherent objectivity of the official measure also explains, in part, why it and other such statistics are occasionally subject to criticism.” Drop the “occasionally,” and that’s still true today! As also remains the case, some wanted a more “narrowly targeted” measure, while others believed the official stats understate the “full dimensions of the unemployment problem.” They note that some look at unemployment rates as a cyclical indicator, while others think of it as a measure of hardship, people who are “suffering because their most basic economic needs are not being met.” But they add that unemployment measures are not a good measure of hardship: income data is needed, and hardship is “usually perceived as a family rather than an individual matter.” That seems a more wholistic formulation than is often heard on the street these days.

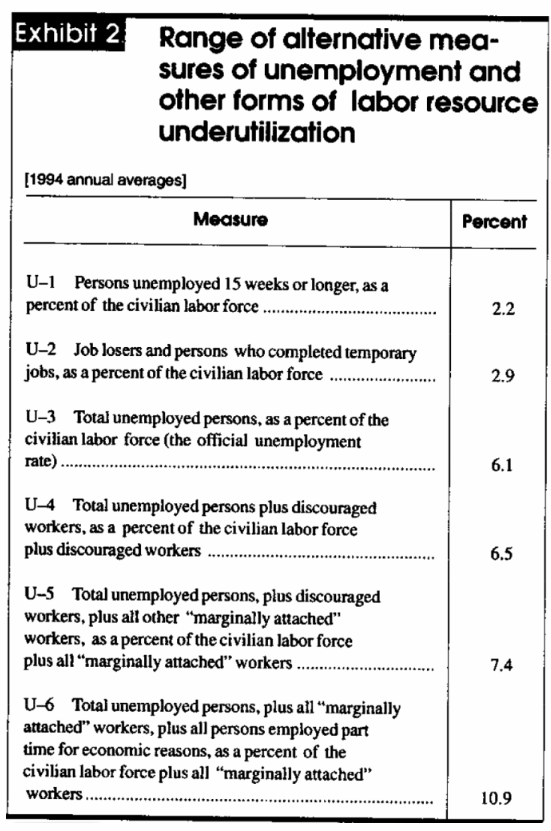

And that’s why Shiskin formulated seven measures. In his words, “No single way of measuring unemployment can satisfy all analytical or ideological interests.” Pictures, even of words, being worth thousands of words, here’s how things were:

and how they are:

Please note that in the old series the lower four measures were independent, “not only of each other but of official measures,” whereas U-6 and U-7 had “additivity” with U-5. Bregger and Haugen end the piece noting U-1 through U-6 represent “useful,” though by no means fully comprehensive, measures of unemployment and labor market underutilization, and that the Bureau “encourages” people to come up with their own sets.

With the BLS under siege, I think I’ll give that a miss! But I do encourage anyone who has the interest to take a look at the pieces. They touch on progressions of terms, like the replacement of depression with recession and the “more neutral” contraction, and the BLS’s efforts to capture unemployment, whether as an indicator or as a misery index. In their last paragraph Bregger and Haugen seem to lament that although there is interest in the alternative measures, it tends to be “fairly narrow,” with users “appearing” to limit their discussion to the contrast between the official and the highest measure of unemployment, passing over the lower rates, instead of gleaning insight from these different ways of looking at the proverbial elephant.

That’s still going strong lo these thirty years later, and, to me, raises the noise level without deepening our understanding of who is not at work, and why.

Thank for your insights, David! Philippa